Patient-Centered Care: A Paradigm Whose Time Has Come

If you ask a neurologist to describe Parkinson’s disease, most will tell you it’s a disease defined by tremor, rigidity, slowness, and stooped posture. A few years ago, we surveyed over 1000 people with Parkinson’s (PwP) and asked them to describe their symptoms--fatigue, impaired handwriting, loss of smell, memory problems, and muscle pain were the most common.¹

I have spent the past few years reflecting on the discrepancy between how patients and providers view this disease. I keep coming back to this idea that PD has been defined by the symptoms that providers can observe, not by the symptoms the patient experiences. Currently, PD is understood and managed from a provider-centered paradigm.

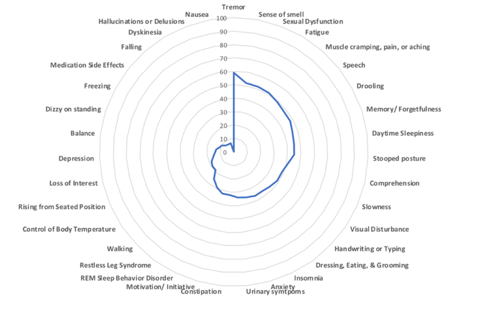

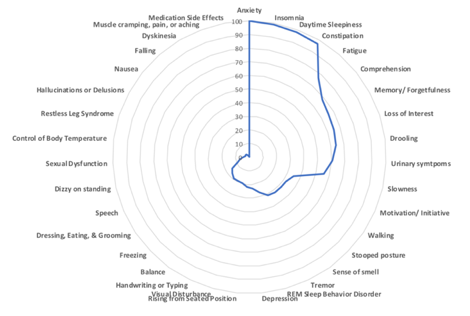

Symptoms of Parkinson’s disease rated as most frequent by 1077 PwP.

According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM), a shift to patient-centered care was highlighted as one of the key targets for developing a healthcare system that meets patient needs. The IOM defines patient-centered care as being “respectful and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”²

What does patient-centered care look like in PD?

In our clinic, before each visit, patients are asked to go to the website www.PROPD.org and rate the severity of their symptoms. (Those that don’t have computer access or literacy are given an iPad or paper version in the waiting room.) The PRO-PD tool allows us to track symptom change over time, identify which symptoms are getting better, which are getting worse, and allows us to set goals specific to the needs of the patient.

PRO-PD Score Interpretation: A zero means you report that you do not have any of the 33 common symptoms of parkinsonism, including non-motor symptoms. The scale correlates with existing measures of PD severity and, most importantly, quality of life. Lower PRO-PD scores are associated with higher quality of life. The average person has a score of 580 at diagnosis and progresses at a rate of 38 points per year.³

Patients are given a card that allows them to monitor changes in symptom severity over time.

In the example above, the patient recorded a more than fifty percent reduction in symptom severity over a 3-month period. (Of note, this patient did not increase dopaminergic medications during this time period. These improvements were the result of diet and lifestyle modification, correction of nutritional deficiencies, and eradication of an intestinal infection.)

The multiple manifestations of parkinsonism

It is well-known that there is a tremendous amount of diversity in PD symptoms. Below are radar charts of two different people with PD- the blue area in the center represents the total disease burden. Symptoms are arranged from most severe to least, beginning at the 12 o’clock position. For the first patient, the symptoms contributing to the greatest disease burden are tremor, loss of smell, sexual dysfunction, and fatigue. For the second patient, anxiety, insomnia, daytime sleepiness, and constipation are the greatest contributors. To bring patient-centered care into the clinic, providers need to be able to understand how the disease manifests in each patient.

Putting Patients in Power

Some strategies for putting patients in the driver’s seat are subtle. For instance, I ask patients to call me by my first name. This seemingly insignificant act of being on a first-name basis translates to an immediate shift in power, allowing us to collaborate as teammates. By stepping down off the physician pedestal, patients step up.

Appointments begin by asking the patient about his/ her goals for the visit. Do they have a list of questions or any specific symptoms they would like us to prioritize? To keep the focus on patient empowerment, patients are asked about changes they have made since we last met. Equally important, patients are asked about obstacles preventing them from meeting their goals and we spend clinic time problem-solving together.

Treat the patient, not the disease

The word “doctor” comes from the Latin word docere, which means “to teach.” While I prescribe dopaminergic pharmaceuticals, the majority of clinic visits are focused on education—addressing nutritional needs, how and where to exercise, how to prevent social isolation, emerging research related slowing progression, etc. I remind the patient that I am working for them; they are employing me to give an opinion. My job is to teach them about the therapeutic tools available to them. Their job is to weigh the potential risks and benefits of my suggestions and decide whether or not to proceed with the care plan.

Perhaps our inability to solve the PD conundrum has less to do with the complexities of the disease, and more to do with the inability of providers, researchers, and patients to coordinate and communicate. As patients find their voice and providers are forced to confront the limitations of our current approach, a shift to a patient-centered paradigm will be essential and inevitable. The future of PD care has to change. My hope is that a team-based approach with patient-centered care will become the new normal.

References

LK Mischley, G Canada, RC Lau, SH Isaacson. Parkinson’s Disease from the Patient Perspective [abstract] Mov Disord 2017; 32 (suppl 2). http://www.mdsabstracts.org/abstract/parkinsons-disease-from-the-patient-perspective/. Accessed October 4, 2018.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001.

LK Mischley, RC Lau, NS Weiss. Use of a self-rating scale of the nature and severity of symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease (PRO-PD): Correlation with quality of life and existing scales of disease severity.

Disclosures

LK Mischley developed the PRO-PD rating scale, which is freely available at www.PROPD.org.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Laurie Mischley ND, MPH, PhD presented at the Fourth World Parkinson Congress in Portland, Oregon. As a clinical researcher, she has worked with the FDA, NIH, and the Michael J. Fox Foundation to administer intranasal glutathione, (in)GSH, to individuals with PD. Drawing on expertise in epidemiology, nutrition, neurology, and naturopathic medicine, she is attempting to determine whether (in)GSH boosts brain glutathione and improves health, which she lectured on at the WPC 2016. She founded the social purpose corporation, NeurRx, that is working to develop a canine-based PD screening tool; developed an outcome measure to assess PD severity; and is author of the book Natural Therapies for Parkinson’s Disease. Dr. Mischley maintains a small clinical practice at Seattle Integrative Medicine focused on nutrition and neurological health.

Ideas and opinions expressed in this post reflect that of the author(s) solely. They do not reflect the opinions or positions of the World Parkinson Coalition®